UDL Case Study: Strategies for Active Learning in Bilingual Classrooms

Introduction

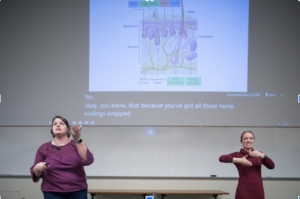

On a typical day, Dr. Sandi Connelly teaches intro level Biology in a large lecture hall to over 150 students. At Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), home to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), it is common to find a mix of hearing students and deaf or hard-of-hearing students in her class. Sign language interpreters are paired with instructors to support students. In her 15 years of teaching, Dr. Connelly has developed strategies to support active learning in large lecture courses for students who have a variety of preferred communication modes. Drawing on the Universal Design for Learning framework (UDL), Dr. Connelly employs case-based learning and collaborates with the interpreters in her class to engage learners.

Case-Based Learning

Cases are representations of real world situations. They can present simple sets of problems, but they can also represent fairly complex problems that require students to read a substantial amount of information, examine artifacts, and use analytical thinking skills. Further, case studies are ideal material to ignite active learning, as it is “student-centered.” As the responsibility for learning shifts toward students, the role of the instructor also shifts, from the conventional authority who dispenses final-form knowledge to an expert guide, who motivates and facilitates the process of learning, while promoting the individual development of learning skills (Alchin & Allen). As a professor who often teaches science to non-science majors, Connelly teaches with case studies to supplement the traditional content. In the video below, Connelly describes how she checks for understanding when teaching cases in large classes.

Universal Design for Learning

Integrating technology and digital media into higher education course material is critical to the implementation of UDL.The UDL framework engagement principle recommends using multiple means for engaging students, acknowledging the importance of “alternative ways to recruit learner interest.”

The multiple means of representation principle and the multiple means of action and expression UDL principle are particularly important in a large lecture hall with hearing and deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Connelly relies on a combination of high-tech (captioned video, FM units) and low-tech systems that do not privilege oral communication over American Sign Language (ASL) to create options for how to represent content and give students choice in how to express understanding. In the video below, Connelly discusses how she allows students to use more than one way to express what they know.

Students attending Connelly’s class are less likely to require accommodations, as she has anticipated their needs by intentionally designing the instruction for all learners, selecting the materials carefully, and creating systems for communication to meet the needs of all her students.

In addition to designing her course materials and approach for all students, Connelly also responds to students' needs while teaching. In the video below, Connelly describes how she adjusts her instruction on the fly and makes trade-offs in covering all the content in order to support student learning.

Working Effectively with Interpreters

RIT/NTID enrolls over 1,100 deaf and hard-of-hearing students, who use a range of assistive technologies and communication modes. To best support learners and instructors, NTID created a checklist to guide instructors to effectively collaborate with interpreters in class — and nearly all of the checklist items align with UDL guidelines. This is not surprising, as the UDL framework and the NTID checklist are in service of a shared goal to create accessible and inclusive learning environments and recognize that learners differ from one another.

The NTID checklist helps instructors consider the pacing, materials, and physical space when teaching in a bilingual classroom. Prior to class, the instructor and interpreter review print and digital materials, availability of captioning for any audio/visual materials, and where the interpreter will stand to create clear line-of-vision for the deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

During the class, the instructor and interpreter are mindful of the need for processing time for the interpreter and students, allowing for pauses between speakers. Additionally, breaks should be built in between topics, and visual materials should remain posted as long as the interpreter needs to refer to them.

NTID offers a free tool, PacerSpacer, a simple visual animation that can be downloaded and embedded into presentation slides. The animation changes color from red, to yellow, and then green. The presenter waits until the animation turns green to begin speaking, allowing time for deaf and hard-of-hearing students to read slides and then focus their attention to the interpreter or instructor.

In the video below, Connelly explains more about how she works with interpreters to support active learning:

Ultimately, Connelly’s goal is to create a learning environment that works for all students. Technology is a critical component of inclusive, active learning. In the video below, Connelly discusses how technology can help her create a classroom community inclusive of all students.

Resources

To learn more about the UDL Guidelines, case-based learning, and teaching with interpreters, check out the following resources:

- Checklist for Instructors Working with Interpreting Services in the Classroom

- Top Ten Things Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students Would Like Teachers to Do

- UDL Guidelines

- Case-based Learning

References

- Case-based learning in science education (Allchin & Allen)

- UDL On Campus

Disclaimer: AccessATE is funded by the National Science Foundation under DUE#1836721. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.